While my early days at DHS were a bit of a mixed bag in terms of discovering who I was and ultimately who I wanted to be, an unpleasant memory surfaced recently that I’m hesitant about sharing…but this is supposed to be a look back on all that I remember, warts and all, so to speak.

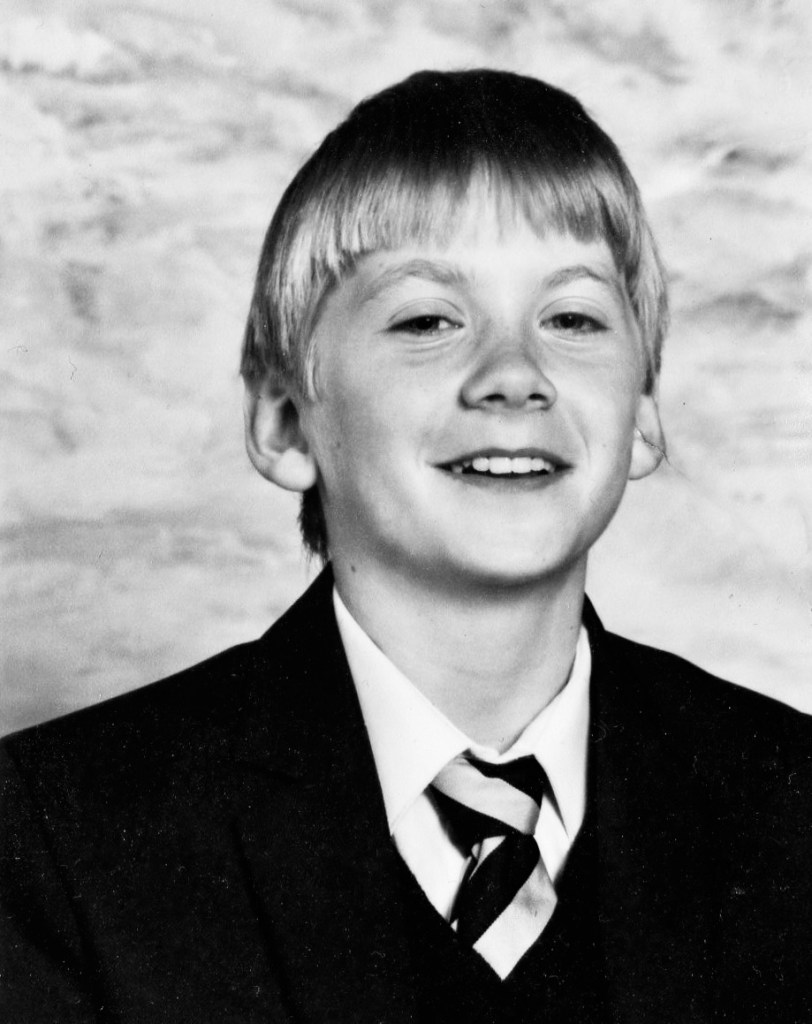

I’ve already considered the fact that I had a gob on me when I was younger and there were occasions during my time at DHS where I earned a well-deserved whack or two from my peers as I traversed the fine line between being funny and being a complete tosser. However, there was one time when I was arguably worse than that, when I crossed paths at our local bus stop with a cheery-looking first year (my gap-strewn memory tells me that he was called Michael Hughes, who we also nicknamed ‘Smiley’ on account of his optimistic and innocent outlook on this new world that he had entered). I don’t remember a huge amount of detail about our encounters, but nothing that I did covers me in any sort of glory. One morning in particular, I was in a bad mood about something (probably impending trouble for not doing my homework) and Smiley turned up at the bus stop looking far too happy for my liking. So, I asked him why he was looking so ‘fucking happy’ and yanked his tie, like many had done to me on a daily basis, which sounds like I’m trying to make an excuse for my behaviour. I’m not; it was a stupid, unkind thing to do and completely uncalled for. I thought little of it at the time, but it upset young Smiley to the point of tears. That should have been the point where I realised my error…

Of course, the fact that I’m writing about this makes it obvious that no such moment of self-discovery took place. In fact, over the next couple of weeks, I probably made Smiley’s life particularly unpleasant. To this day, I couldn’t tell you why. Even the most amateur of psychologists would tell you that I was probably deeply unhappy with myself, which I was. You certainly wouldn’t need any qualifications to work that out if you’ve read this far. But what possessed me to take it out on a random twelve-year-old lad who never did me any harm? I obviously lacked the maturity to have those thought processes back then and I am deeply embarrassed and ashamed of my behaviour. You will be pleased to hear that justice was swift and effective.

I soon got wind of the fact that ‘Smiley’s Dad’ was after my blood. I had already clocked him from Smiley’s first few days of catching the bus, walking with his son on his new, big adventure and seeing him off to school safely, which, with the benefit of age and wisdom, I now see as a wonderful thing to do. To a group of gobby teenagers, however, it was a bit weird and overprotective. None of my business in the grand scheme of things though.

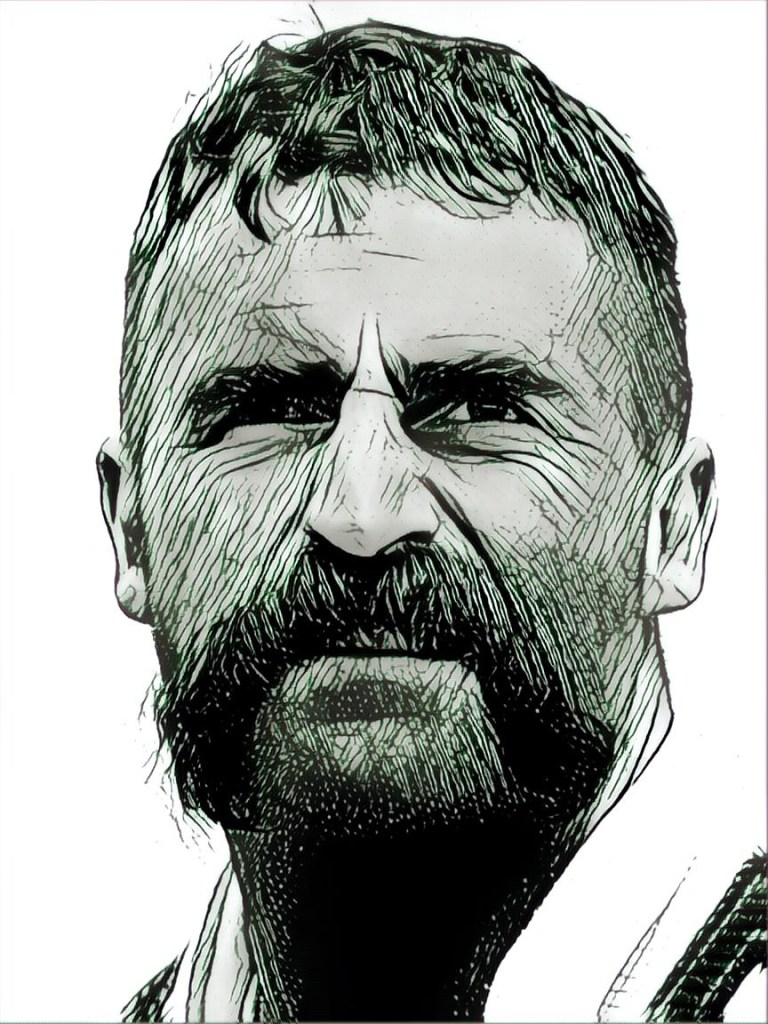

But back to Smiley’s Dad. He looked, through the hazy reminisces of time, a bit like the maverick Aussie fast bowler, Merv Hughes, but with longer hair that was flecked with wisps of grey that suggested he was clinging to middle age despite Father Time’s best efforts. He also looked like the sort of man that you really didn’t want to piss off, so by the time I discovered that I had done exactly that, there began a cat-and-mouse situation where I would avoid taking the bus, instead making the mile-and-a-half journey to school on foot.

After about two weeks of this, I lost patience and let my guard down, convinced that everything would have calmed down and that, in the grand scheme of things, it hadn’t been that bad anyway. What I didn’t reckon with was the fact that Smiley’s Dad was infinitely more resolute than I was. Sitting on the top deck of the bus, I was horrified to hear the excited cry of ‘It’s Smiley’s Dad’ from below stairs and even more terrified when the parent in question came snarling towards me like a hungry wolf who had finally cornered his prey. He grabbed me by the shirt collar and dragged me towards him as my arsehole threatened to expel my breakfast.

‘Think it’s clever to pick on someone younger than you, do you?’ his eyes bored into my very soul as I shook my head vigorously, any bravado that I had previously possessed failing to put in an appearance for good reason. I genuinely thought that he was going to hit me and I’ll be honest, I wouldn’t have blamed him if he had. The tirade continued and he made it very, very clear what would happen if I so much as breathed in the direction of Smiley from that moment on. I nodded furiously when he asked if I understood before he pushed me back against the window of the bus and strode away, through the crowd of silent onlookers. I said nothing, dwelling on the stupidity and cruelty of my own actions. I had well and truly got what I deserved and even after all these years, I can’t make a case for my behaviour. Suffice to say, I didn’t go anywhere near Smiley for the remainder of my time at DHS and on the few occasions that I saw him, he would give me a smug, knowing smile. Fair play to him.

I think that perhaps we don’t realise the implications that our words and actions can have during those difficult teen years. I’m certainly not trying to justify any form of bullying, there was an awful lot of it around at school, some that got dismissed as ‘banter’ and some that was far more serious.

Back then, I suspect that many incidents of that nature were dealt with in a similar way, which was obviously incredibly fruitful in terms of putting a stop to the behaviour. Did it educate me? No, it simply put the fear of God into me to make sure that I wouldn’t do that sort of thing again. Some might say that was education enough and they may be right. In time, however, what has been far more effective is the understanding that I made somebody feel exactly the way that I was made to feel during much of my childhood. It’s relatively easy to make light of the interaction with Smiley’s Dad, to laugh it off as ‘one of those things’. What doesn’t go away is the shame of having behaved like I did – even after thirty-odd years, so I suppose that there are short-term and long-term punishments. Either way, those were not my finest days.

At the risk of sounding incredibly old, it’s relevant when I say that at DHS, these were the days of blackboards and heavy chalk dusters, the wooden ones. It will surprise nobody to learn that even back then, riddled with insecurities and nervousness, I was partial to the odd chat or two. I received a detention (one of many) along with three or four others and the punishment was being overseen by the fearsome Mr Borbon, who lacked all of the sweetness and associated qualities of the similarly named biscuit, instead ruling classes with a stare that could curdle milk at a thousand paces and a temper of volcanic proportions. He also possessed, it turned out, a surprisingly accurate throw as I was soon to discover. Mid-conversation, I saw a movement in my peripheral vision and was fortunate to realise in an instant that the chalk duster was travelling rapidly towards my head. I was so, so lucky that I caught it, inches from my face, as it could have caused some serious damage. However, my lucky escape and sharp reflexes only served to enrage him further and he marched over to the table and dragged me from the classroom, depositing me unceremoniously on the floor outside and unleashing upon me the mother of all bollockings.

All of the above probably makes it sound like I was the sole perpetrator of misbehaviour in my classes, but nothing could be further from the truth. We could be quite brutal as a group and the entertainment that we conjured up during wet break times was violent, bordering on barbaric. I have no idea who came up with the idea for ‘Death Trap Alley’, but it was horrific.

The basic idea was that we would drag two rows of tables to face each other, leaving an ‘alley’ about three feet wide that we would have to fight our way through from one end to the other, while anyone who had already navigated the ‘alley’ would take their place on one of the tables and kick the living shit out of the next participant as they tried to battle their way through what was basically group-perpetrated physical assault. The trick, and by using the word trick I am by no means trying to make light of the process, was to get through as early and as quickly as you could. The longer you left it, the more people were involved and the number of injuries available to you would thus increase.

Similarly, we’d have games of Pontoon (also known as 21), but the losers of each round would have to cut the cards and whatever number was on the card that they uncovered would dictate the number of times that they would get hit over the knuckles with the full deck. If you drew a red card, you would receive relatively gentle hits, but a black card…well, the Kings of Clubs and Spades were feared for very good reason. This game, if I recall correctly, was known as ‘raps’ and would regularly lead to injured hands and bleeding knuckles.

Birthdays were no less traumatic and one of the few areas of my life where I could count myself ‘lucky’, as during four of my five years at DHS, my birthday fell during the October half-term. Those less fortunate than I were ‘treated’ to the bumps (face-down) before being thrown joyfully down the steep bank towards the playing fields. Some way to celebrate!

Despite my predilection for landing myself in hot water, there were a few teachers during my time at DHS who would occasionally offer support and encouragement. I recall enjoying French lessons, not because I had any particular affinity with the subject but because the teacher in question, Mr Jones, seemed like a really decent guy. He didn’t mind the odd joke if it didn’t go too far and he was thoughtful in his explanations – I’d say he was ahead of his time in understanding the differences in learning in individual students. Compared to my French teacher in my first year, Mrs Pierpoint, who called me out immediately in front of the whole class for daring to find humour in the pronunciation of the word ‘droit’, Mr Jones was a gift that seemed heaven-sent. I can still recall Pierpoint’s disparaging voice even now:

‘Ha, ha (she actually said the words ‘ha, ha’), very funny. Hepburn thinks that the word ‘droit’ sounds like twat.’ I did, and after that particular incident, I thought of a few extra words that Pierpoint might be a translation of.

I’ve always loved History and although I didn’t excel at it, I would try to do my best and enjoyed lessons with Mr Almond, who, if I remember correctly, was also involved in the Drama department and gave me the starring role in the 1st year production of A Christmas Carol. I’ve retained a love of looking back into the past and could have done far better than I did in History with the proper guidance and support. It remains a source of frustration that I didn’t manage to apply myself better.

I was fortunate enough to never have a bad English teacher and although I ended up in the bottom set, Mr Bowden was probably the best teacher for me and the one who allowed me to express myself most. I would regularly turn in lengthy (no surprise there!) essays and poems full of the most fantastic and outlandish ideas and always felt supported in his lessons. The best piece of work that I ever presented, a poem about winter, was marked at 92% and although I no longer have a copy of it, I remain incredibly proud of it. Probably sounds daft, doesn’t it? But as a perennial underachiever, who generally thought that everything they did was shit, that piece of work was my hope. My future.

The one thing that overshadowed every lesson that I took part in was an absolutely horrendous lack of self-belief, which I still carry with me to this day. I would sit in class dreading being asked questions and even in situations where I was confident that I knew the correct answer, there was no chance that I was ever going to raise my hand to issue forth my thoughts. In the classroom environment, I always felt small and insignificant and I’d rather sit quietly and let people assume that I was stupid than run the risk of being right. Being wrong would have been far, far worse, although so many of those fictional scenarios played out in my head would probably never have taken place. But I guess that I was a ‘safety first’ person and deep down, I suspect that I still am.

I had a natural antipathy towards figures of authority, likely fashioned from an existence where I was constantly being reminded that I was nothing, but two teachers managed to buck that trend, albeit occasionally and on a temporary basis. Deputy Head, Mr Faulkner, who could regularly be seen dashing along corridors, black cape flying behind him like an educational superhero, always speeding off in search of the next problem that needed a solution and occasionally fearsome yet always fair, Mr Burrows, who I recall possessed a moustache that would have made a Walrus proud and a wicked sense of humour. When I inevitably ended up sent in the direction of either teacher, they recognised that reason over rage was the best way to appeal to me and I’m sad that I never got the opportunity to thank them for their efforts – ultimately, my decision to leave Plymouth straight after my exams was hastened by the knowledge that I had underperformed and that once my father realised quite how badly I had done then I would be unavoidably in for the high jump, and I’m not talking about athletics. When you’re not necessarily one of the shining stars at a high-achieving school, it’s easy to just become a number. Worse still, if you are deemed to be difficult, you can feel lost, all at sea in a broiling ocean of uncertainty. I’d like to think that Mr Faulkner and Mr Burrows recognised that and did what they could to keep me afloat.

That performance of A Christmas Carol that I mentioned is also something that I was really proud of. With more confidence and support, I think I would have pursued an acting career, but the emphasis was always on getting a ‘proper job’. In my first major foray onto the stage (my only previous experience was as a wise man during the nativity play at Inverteign, carrying myrrh for those who might be wondering!) I somehow landed the role of Ebenezer Scrooge and I loved it! It’s my favourite of all Dickens’ works and I really threw myself into the role. I learned my lines obsessively, to the point where I didn’t make a single mistake during the entire performance and fully committed to the costumes, one of which was an old nightie that belonged to my younger sister, Ellie that I had to don during the ghostly visitations. ‘Scruffs’ at DHS weren’t generally well thought of; fewer still would earn the appreciation of their elders, but at the end of the performance in front of the whole school, we received an enthusiastic ovation and for a few weeks after, I would get the odd nod of approval while scurrying beneath the colonnade in direct contradiction of the ‘no running’ rule. The opportunity to be someone else for just a few minutes was something that hugely appealed to me; I could cast off my inhibitions, my insecurities and my past. I don’t have many big regrets, but I suppose this might count as one. Hi-diddle-dee-dee. An actor’s life could have very much been the one for me.

Copyright Alec Hepburn, 2026.

Leave a comment