Football at Bishopsteignton was a big thing for me. I suppose that I was a bit unusual in that I could use both feet, so would often be employed at left-back in the absence of anyone else who was genuinely left-footed. I was stronger with my right, but was comfortable enough with the ball at my feet to not need to just use the one foot. We took part in a number of six-a-side tournaments, winning a couple and I think I’ve still got one of my medals somewhere among the multitutde of boxes of paraphernalia that I’ve collected over the years. We had a decent team, with Christian Cook in goal, I think Justin Bannister in defence and Cameron Groves in midfield/attack. From memory, Cameron was a very talented young player but sadly, I have no idea what happened to any of my teammates after I left.

I’ve never been very good at keeping in touch with people, something I’m told that nowadays suggests that I have issues with object permanence, a more concise way of saying ‘out of sight, out of mind’. This has continued to plague me throughout my adult life. I’m quite a solitary person and it doesn’t take much for me to convince myself that if I don’t hear from people, they probably aren’t that interested in spending time with me or communicating with me anyway – I mean, I’m me, so why would anyone want to socialise with me and my associated issues (horrendous overthinking and social awkwardness while keeping a constant vigil anticipating the next sign of trouble). Even though I know it’s illogical, it’s so deeply rooted inside me that it’s one of the few habits/issues that I’ve really struggled to overcome. It could easily be solved by just messaging friends, couldn’t it? Even more so in this day and age, but when you’re convinced that you’re not worthy or even likeable, it’s a very slippery slope to attempt to surmount. I suppose in some ways that it’s partly tied up to that loneliness I felt during those long evenings in pub gardens or any number of similar incidents that I experienced as a child and I find it difficult to talk about because I feel that it makes me appear needy or as though I’m searching for attention. Nothing could be further from the truth. But once again, I digress. Back to the football.

There was one game that stands out in my memory, a home game up on the pitch that sat atop quite a steep hill, which made it ‘fun’ when the ball got kicked out of play on one side of the field. During the game in question, we were attacking but I was hanging back on the halfway line when the ball was cleared up field in my direction. I waited patiently as half a dozen or so boys ran en masse towards me, bunched together as was often the case in primary school football. As the ball dropped, I swung my right foot at it, lashing it skywards more out of hope than anything else and watched in stunned silence as it arced up and away, clearing the opposing goalkeeper and sailing into the net. I didn’t score too many goals in my time, but that was probably the most memorable.

There was another game where we were battering the opposition and we won a corner on the left. I’d been told that I was on corner duty, so I swung the ball into the middle of the penalty area and stood watching the melee that followed until one of our players scrambled the ball over the line. The whistle blew, which at first I thought was to indicate that a goal had been awarded, but our teacher and referee, Mr Dunn, with his tufts of fluffy, white hair sat either side of a bald patch the size of Bulgaria (I offer my humblest apologies if my memories of Mr Dunn’s appearance are misplaced, it’s been an awfully long time and so much has happened), instead chose to give offside against me as I hadn’t moved from the spot from which I had delivered the cross and by the letter of the law back then, I was offside, despite the fact that I could hardly be deemed to be interfering with play from where I stood. I wonder if the game had been a tighter affair whether or not he would have made the same decision.

Around the time of that game, along with Christian and Cameron, I was invited to play for the county side. I was reliant on a lift but we got delayed on the way and when I arrived at the game we were already losing and it was approaching half-time. I had little time to warm up and prepare before being thrown into the fray and while I didn’t have a bad game, I obviously didn’t do enough to warrant being selected again. Had I not turned up late and been able to prepare properly things may have been different, but ultimately I was never much more than a useful player, certainly not a standout, but I loved the game and that was good enough for me.

We did make it to a couple of county cup finals and I remember the morning of one game where I had spent the previous night throwing my guts up with a raging temperature. I was never allowed days off school, but even if it had been on offer, I wouldn’t have missed the final for anything. I somehow dragged my body off my sick bed and played three quarters of the game before being subbed and promptly vomiting at the side of the pitch. We lost 4-2 and I was absolutely gutted when I was told by the teacher that I shouldn’t have played because I was sick. It was the only time that I was ever disappointed in Mr Dunn but on reflection I suspect he was as disheartened by the defeat as we all were. I think it also reflected my own frustration as I felt that I had let him down.

My time at Bishopsteignton came to an end around eight months before I was due to head off to secondary school, I think. By this time, Dad, who was back in work at a nursing home in Newton Abbot, had started seeing Brenda, who would go on to be his second wife. Things were changing at home and a far bigger shift to our circumstances was on the horizon. I think that he was offered a job in Plymouth by an old friend of his, Alex Campbell, so we packed up our belongings and we said goodbye to the village of Ideford (even writing about it now makes me feel sad). One thing that didn’t properly register until many years later was that we left Korky behind with our former neighbours. She was in her twilight years by then and the new flat that we were moving to didn’t allow pets. I hope that she was happy during the remainder of her life and that she managed to avoid particularly woolly and hazardous jumpers.

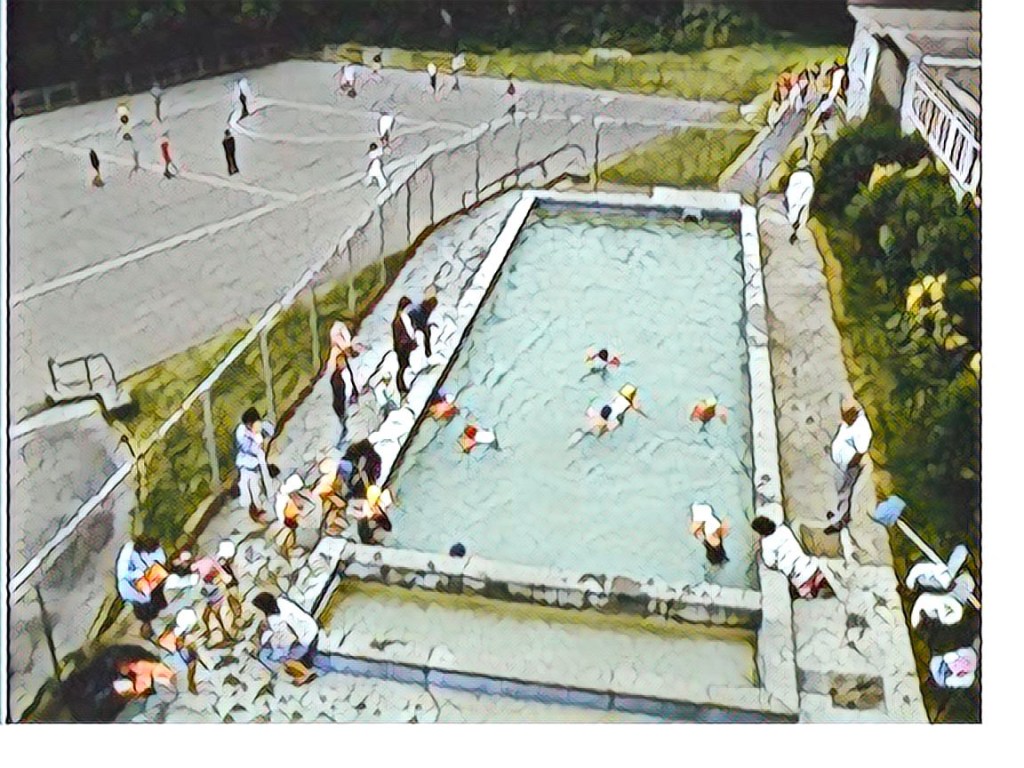

My new school, Pennycross Primary School seemed nice, although it took me some time to settle in. It was here that I finally learned how to swim, by no means an easy task given my previous troubles in water, but with the aid of several floats and an understanding teacher, I somehow managed to complete 25 metres of the school pool, crawling along with the equivalent of an aqua Zimmer frame and not a little humiliation before finally managing to progress to 50 metres without the need of flotation devices.

I went straight into the school football team upon my arrival and in my first game I managed to score a spectacular own goal, putting in a full-length slide in a watery puddle to intercept a through ball only to divert it past my own goalkeeper and watch in horror as it trickled over the line, sodden shorts riding up my arse crack to complete the somewhat pathetic scenario.

Following my move to the new school I took and passed my 11 plus, which gained me a place at Devonport High School for Boys, news which thrilled my dad far more than it did me. Having already studied at four schools by this time, the prospect of another ‘fresh start’ wasn’t really doing much for me.

After a couple of months in a flat at Mount Gould, we moved into a house opposite Pennycross Primary in Springfield Crescent – adjacent to the place where dad would be working, a home for mentally handicapped children that the kids in my year at school had ‘affectionately’ and horrifically nicknamed ‘The Mongol Mansion’. The house was nice enough and the big green opposite was useful for games of football and cricket. It was also a relief to be living so close to school after the endless bus journeys to and from Ideford. It took some adjusting to living in a city and once again having to try and form new friendships.

By far my most exciting discovery at Pennycross, was the fact that there were girls at the school and some who were occasionally mildly amused by my irresponsible and immature shenanigans. Neither did they seem to find me as repulsive as I thought I must be, which opened up a vast and daunting landscape to traverse. There was one girl in particular who I took a shine to, Joanne Kenny (time has dimmed my faculties in the last 41 years, the Joanne may have been missing an ‘e’ and her surname may have been Kelly but I’ve gone with what my instincts tell me is correct). In my mind’s eye, she was slim and of a similar height to me with long, brown hair and an intelligence that burned fiercely behind keen eyes. I feel reasonably safe in the assumption that she probably remembers little to nothing of these events, but they stuck with me because again, I look back disappointed in the way that things transpired. I think we had arranged a date, which for two eleven-year-olds back in 1985 probably involved going into Plymouth City Centre and generally mooching about the place. To say that I was inexperienced in such matters would be a huge understatement, but nevertheless, I was excited by the prospect of taking a real, live girl out for the first time.

Before the prearranged date took place, however, fate intervened, in the shape of one of my few friends at my new school. I’m not going to name him, but he took me to one side to share some ‘important information’ with me ahead of my keenly-anticipated rendezvous with Joanne. He told me, in the strictest confidence of course, that Joanne had epilepsy (foreshadowing one of my darkest days in the future). Despite being the child of parents who worked as nurses, I had no idea what this was or how it presented, so my friend kindly gave me the details as best as he knew them, asking if I’d considered what would happen if she had a fit while we were out together, which might lead to serious injury or worse, death. Obviously, I hadn’t and my normally loquacious self was stunned into ponderous silence. If I’d possessed even half a brain cell back then, I would have asked Joanne about it, but in my perceived wisdom, coupled with a resurgence of crippling self-doubt, I decided that it would be rude and disrespectful to seek such information and by far the best way of dealing with any potential danger or discomfort for either myself or Joanne, was to simply not turn up to the date.

I can almost hear you, dear reader, calling me a prize twat as you take this in. I think it myself. Joanne was inevitably furious and it was only after a robust exchange of views, mainly hers, that I realised quite how badly I had fucked up. There I was, socially awkward, lonely and misunderstood for much of my life and the first time that someone had given any inclination that they might like me, I’d acted like a complete knob. In fact, I’m not even sure that Joanne did have epilepsy and somewhere deep in the furthest, most repressed corners of my memory, something lurks to say that she didn’t and that my friend had advised me so readily because he was also carrying a torch for her. In the grand scheme of things, these fledgling flutterings of romance likely amounted to nothing other than a distant memory for me, who spends far too much time recalling such events and a random story told in a book that the other two protagonists will probably never read anyway. Which probably sums up my life in a very complicated and misshapen nutshell.

Aside from the previous incidents, I remember so little of my time at Pennycross, save for a rather strict teacher named Mr Barrett, whose wrath I recall incurring at some point, probably due to my inability to keep my cavernous gob shut. What didn’t help, was that Mr Barrett looked a little like the American actor, Geoffrey Lewis, who played Mike Ryerson in the 1979 miniseries of Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, which I saw on first broadcast in the UK in 1981 (I think!). It terrified the shit out of me but instilled in me an absolute love and fascination with horror.

A few months later, I saw Mr Barrett on a bus into Plymouth city centre and we had a conversation that changed my opinion of him. It’s so easy to just see teachers as professionals in education and I wish that I’d thought more about this during my schooldays. I would imagine that I was probably quite difficult to teach and my time at Devonport High School did little to dissuade me of that notion even to this day. I was by no means the worst behaved in any class but I had developed a simple approach to each subject that I studied. If it interested me, I would work hard and if it didn’t, then frankly I couldn’t be arsed. Sadly, I didn’t possess the skills to keep a low profile and do what was necessary to avoid getting into trouble. I was easily bored and loved to make people laugh, so whenever the opportunity arose to entertain my peers, I generally seized it.

Sometimes I would get away with it and teachers would be momentarily amused and other times my mouth and glib sense of humour would bag me a detention or two. Looking back, I could and should have done more and worked harder, although I’m not convinced that I would have ended up anywhere else other than where I am now. Ultimately, I think that I was always supposed to either end up in sport or become a writer and I believe that I’m fortunate to have found myself with the opportunity to dabble in both areas! Whether or not I’ve been successful is for others to judge, but both career paths have given me moments of happiness. For someone who is not blessed with confidence or self-belief, that’s generally as good as it gets! However, now that my time in cricket has come to an end, I look back with mixed emotions, hoping that in time the good memories will outweigh the bad. If nothing else, that time has given me more stories to tell.

Copyright Alec Hepburn, 2026.

Leave a comment